Academic Success For Sale

HOW SCALPERS AND IMPERSONATORS PROFIT FROM ACADEMIC FRAUD

While most students are struggling to enroll in classes and earn their A’s, some students at Santa Monica College have managed to purchase their guaranteed success, gift-wrapped in packages for thousands of dollars. For a price, these students can pay to enroll in “easy-A” courses and even skip school -- paid impersonators could take their courses for them.

Illustration by Diana Parra Garcia

“My first semester here, a student in an English 1 class invited me into this group,” says XingChi Wu, an SMC student. According to Wu, who has not been found involved in these unethical activities, some students use a social messaging app called WeChat to provide information about housing, furniture, and resources that help their transition into a foreign country. Yet its primary function is more adverse -- it serves as a network for buyers and sellers to exchange services of selling popular course seats and impersonating for other students.

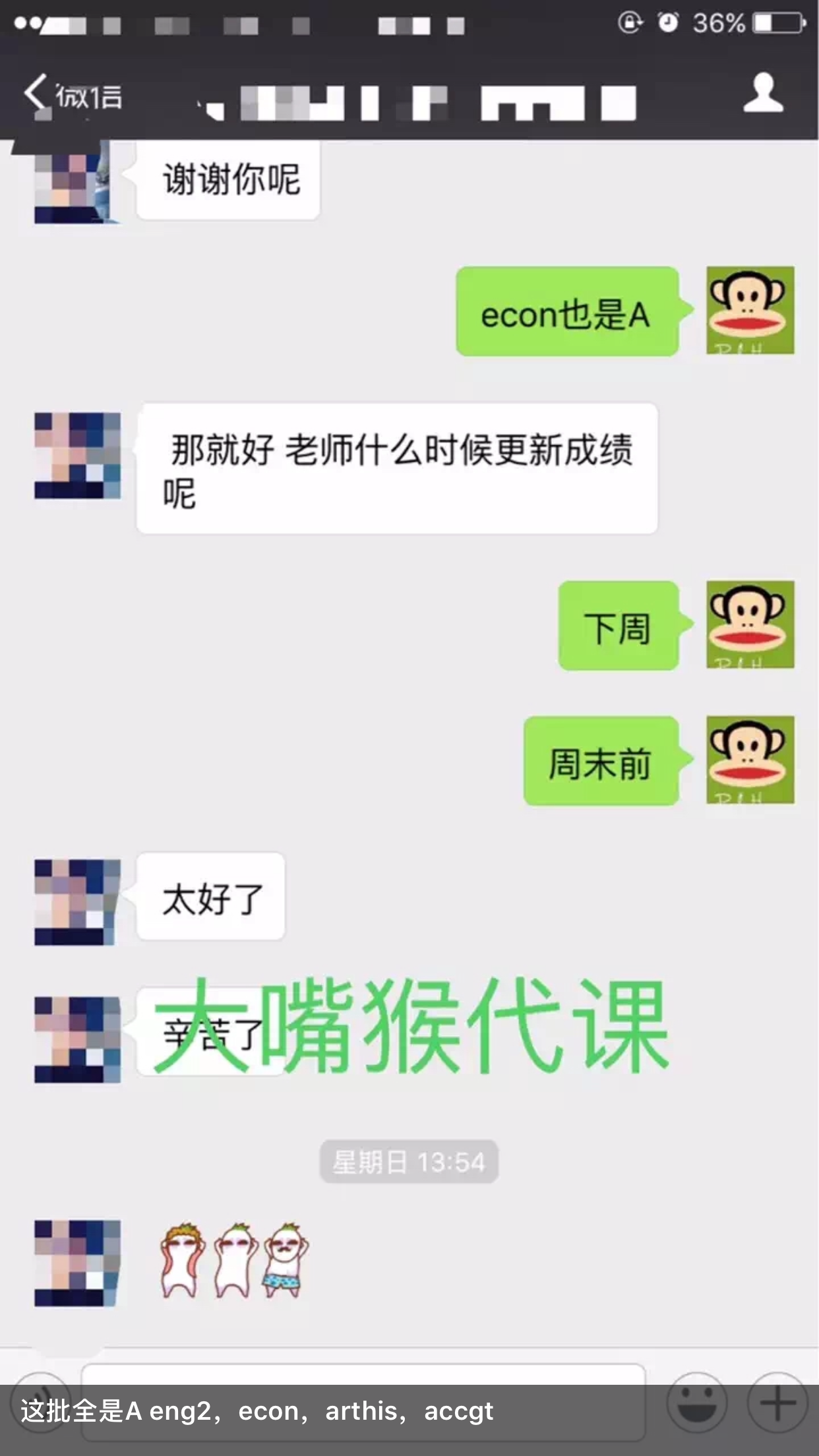

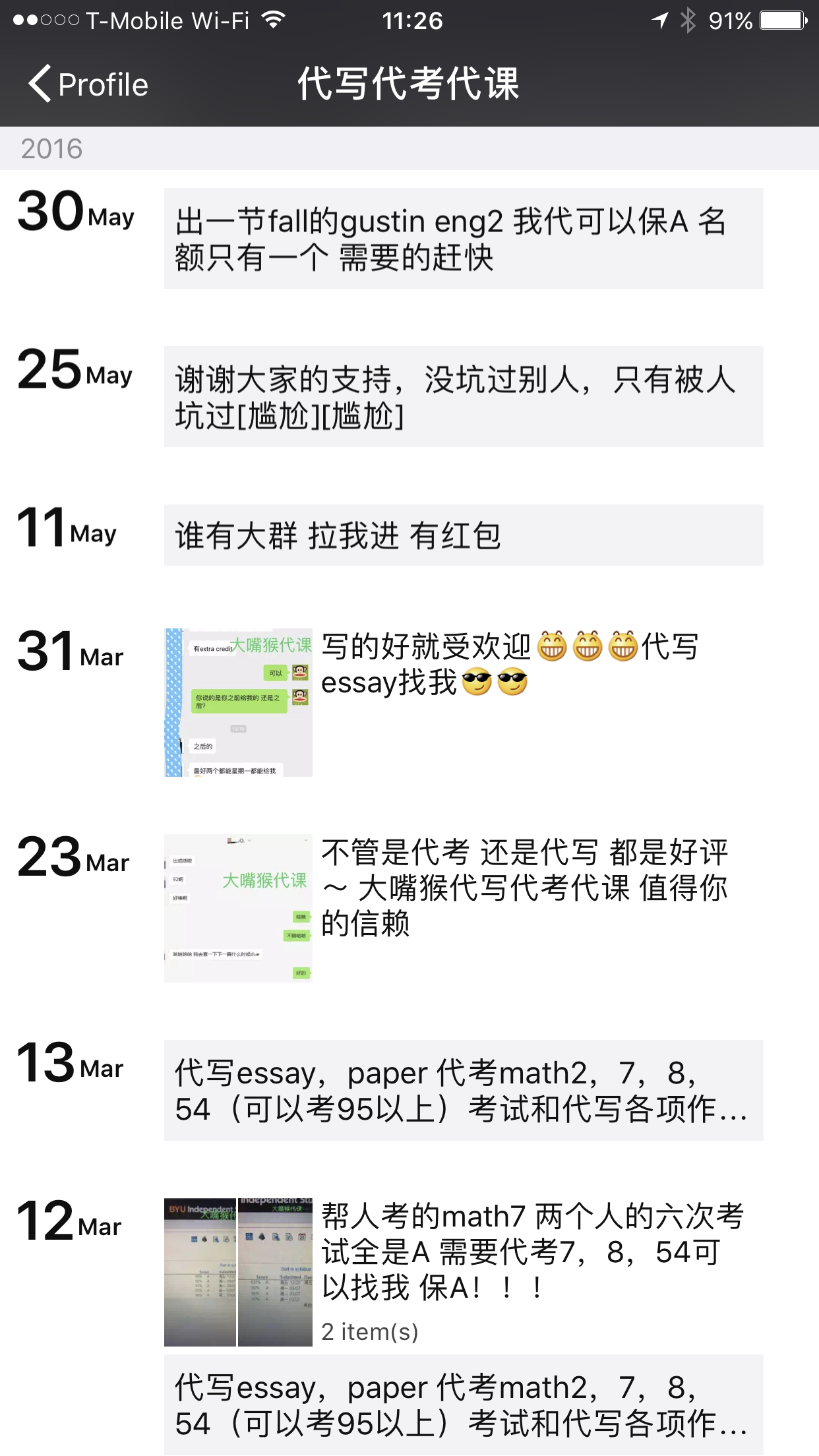

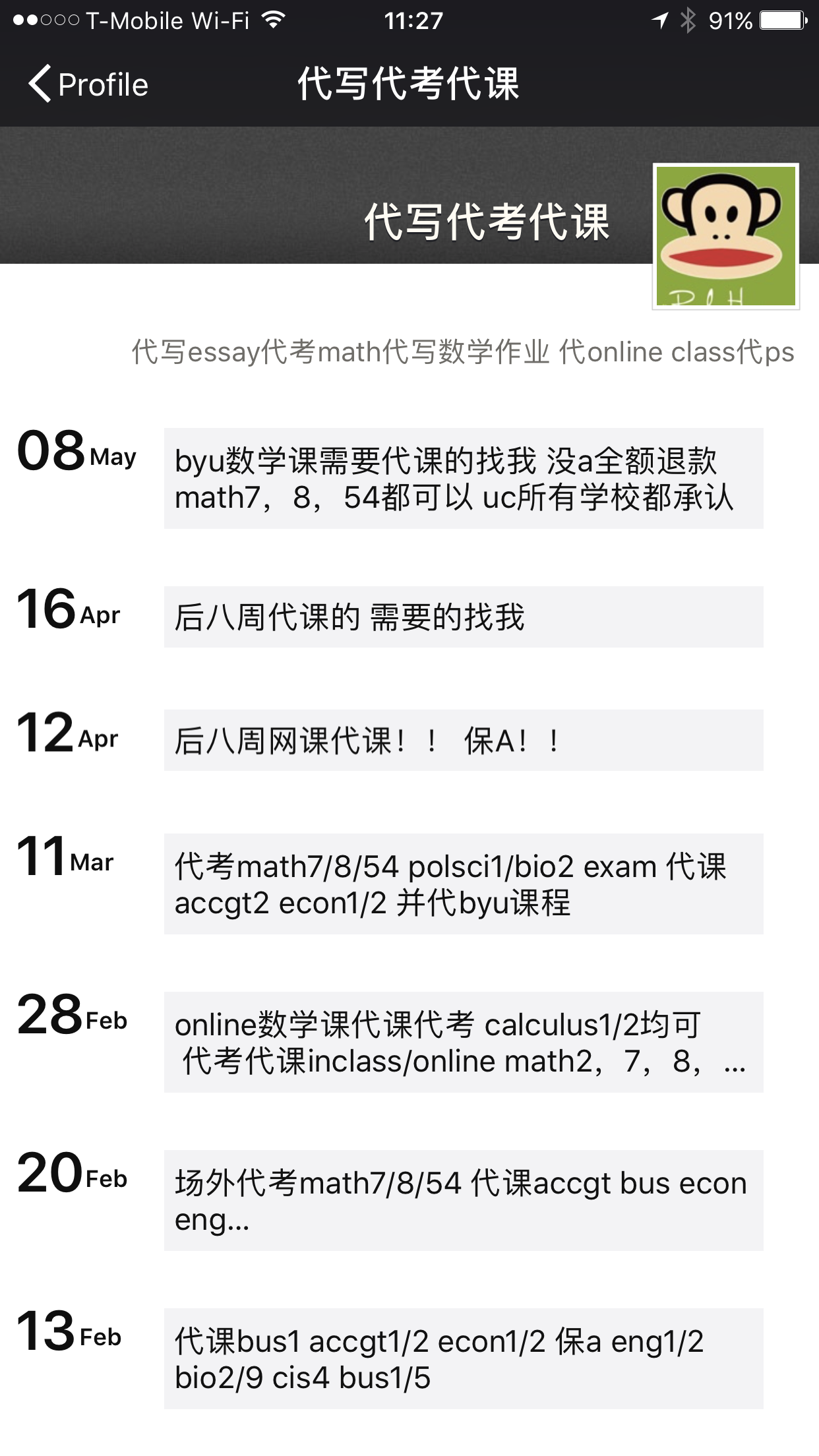

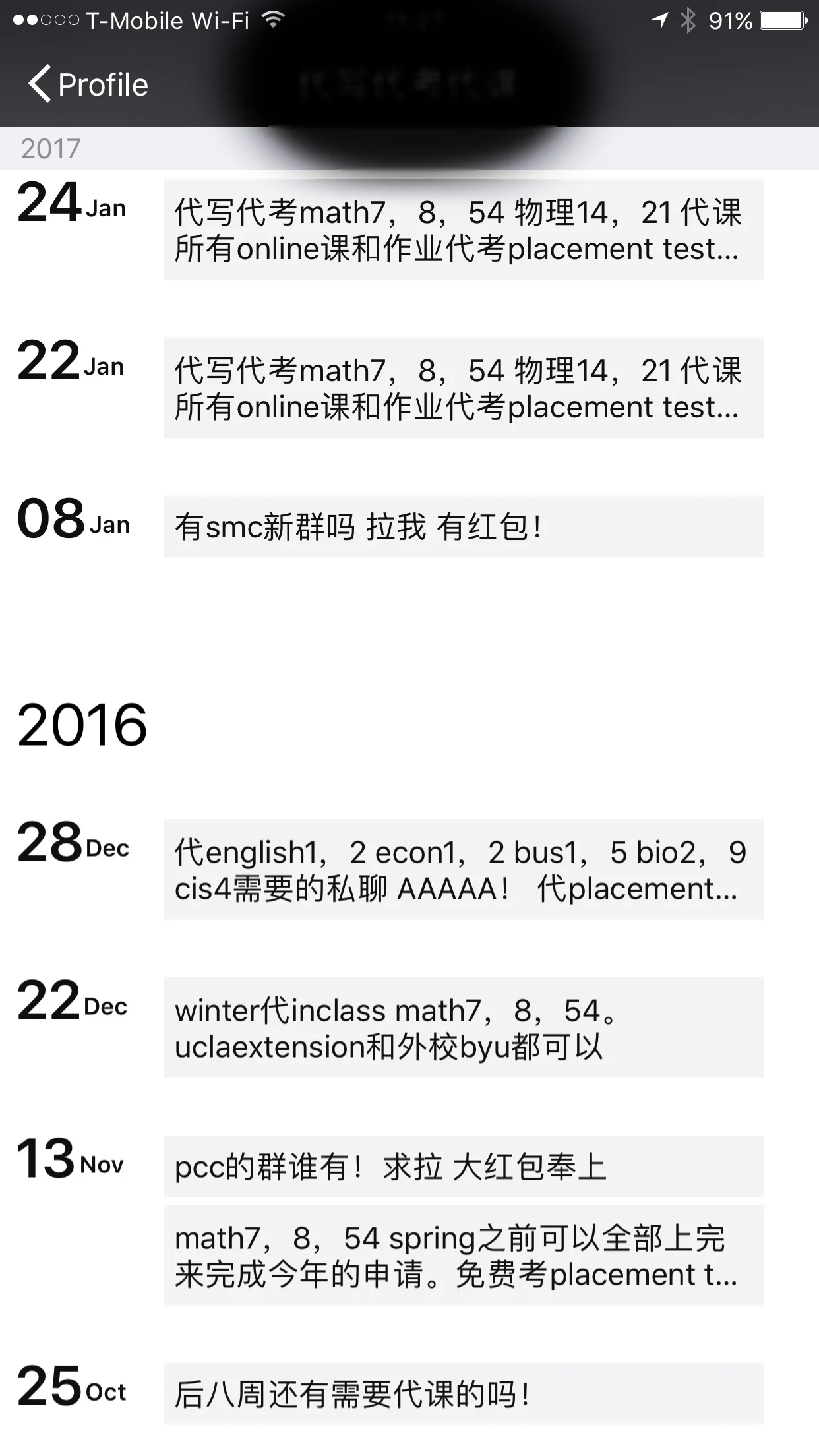

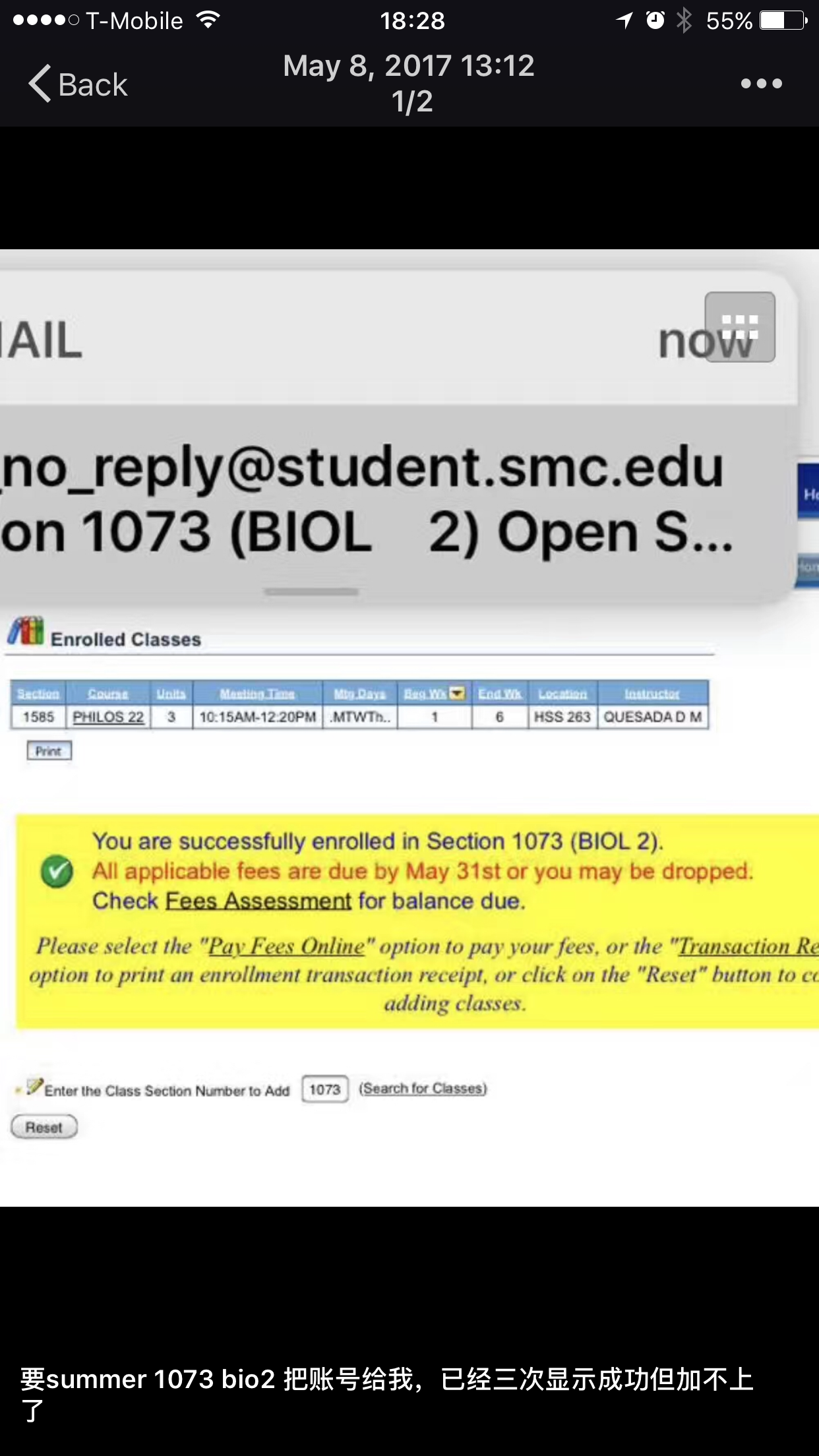

The “impersonation” services consists of customers paying a premium to have students, even alumni, take courses for them. Most of these services are offered for online courses for UCLA Extension, Brigham Young University, and Santa Monica College, yet bolder sellers have even advertised to impersonate students for classes on campus. Some, as depicted in the pictures online, even provide money-back guarantees. Other interactions include the buyer saying ,”I will transfer money to you in a moment.” The seller, using the username “Big Mouthed Monkey”, openly says in his advertisements, “I will take lesson for you in English 2. Got an A... if you need me to take a class for you, look for me.”

SMC finds these impersonation services to be a more serious and long-standing issue than scalping. Deyna Hearn, the Dean of Student Life at Santa Monica College, recalls a time when the issue was more prominent, saying, “several years ago, the former president of the college [Chui L. Tsang] had us put together a task force to look at impersonation particularly.” The impersonation is the same activity as impersonation, where students can pay to have others take the classes for them. Hearn continues, adding, “we brainstormed on some things and... got a recommendation from the committee for a minimum of two-years suspension for some forms of impersonation.” She immediately stressed that not every person who impersonates for another gets suspended, as it depends on the scale and type of impersonation. After these meetings with the committee, Dean Hearn’s office continued to increase the years of suspension, which she claims caused these impersonations to decline. She admits, “It’s not to say that students were no longer doing this, but word was getting out that these will be the consequences if you got caught.”

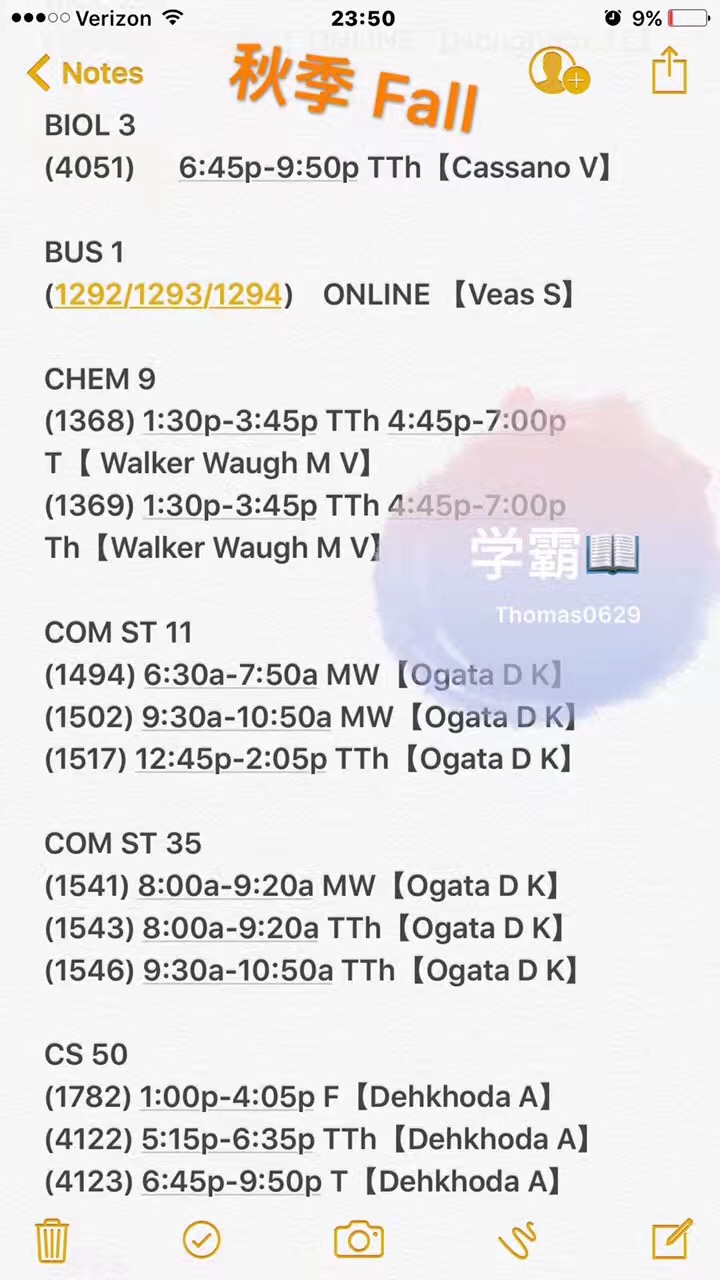

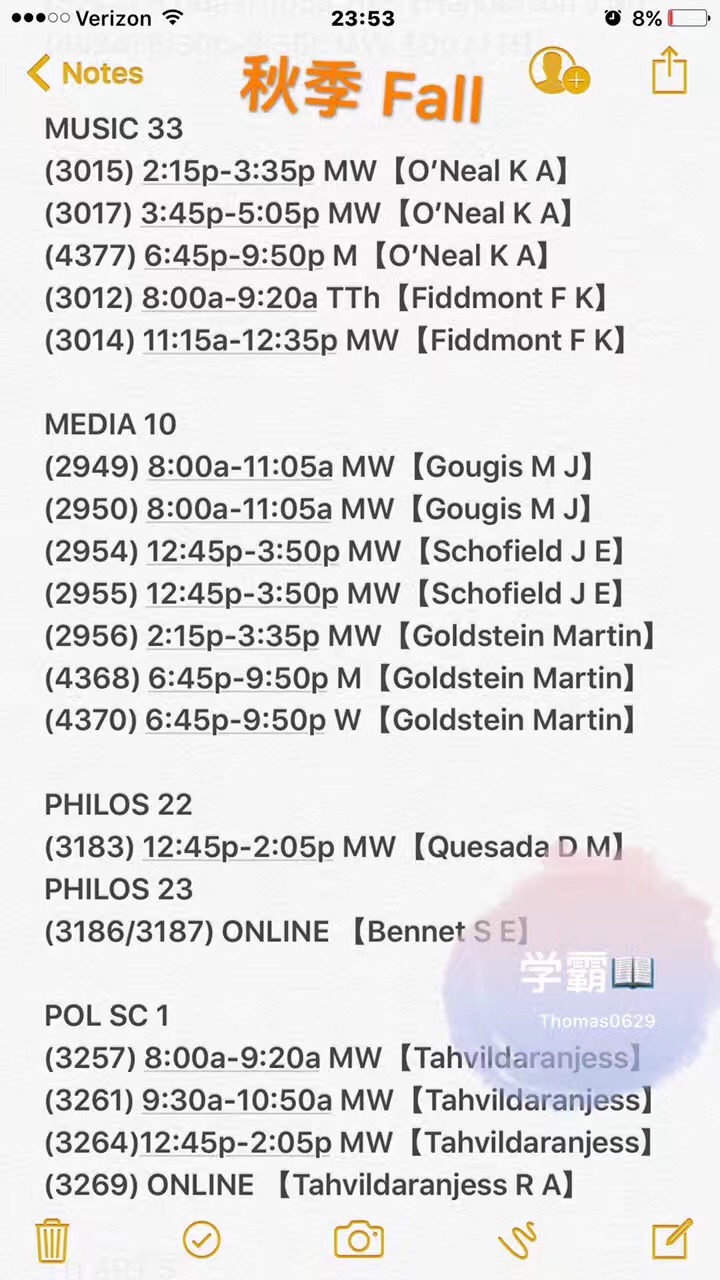

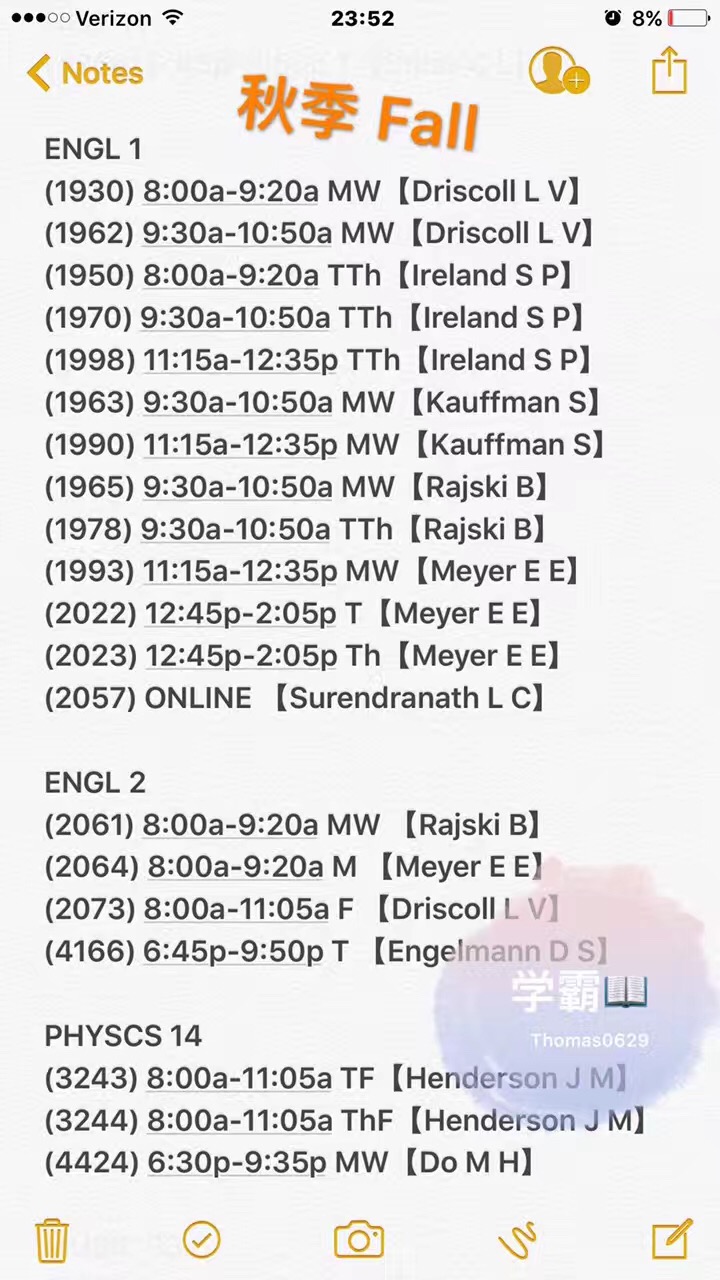

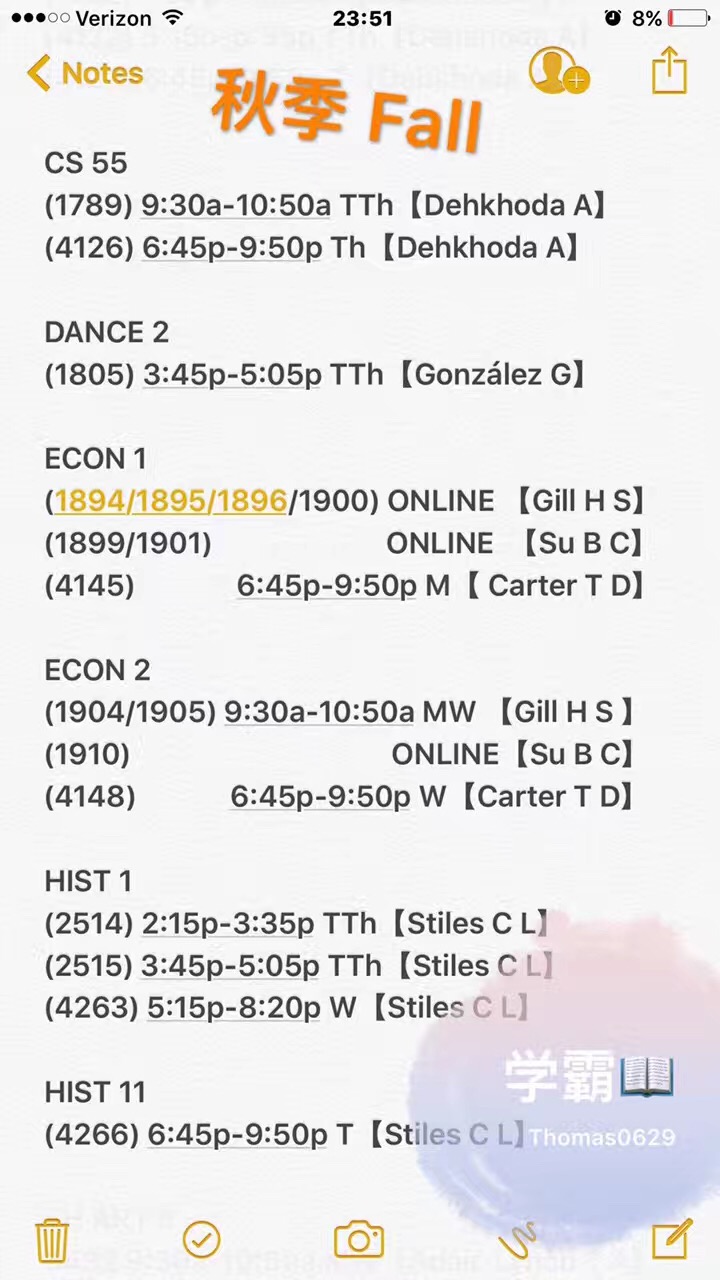

But the scalping, or selling, of popular courses is a more recent development that has been more difficult to discover. Student rings have scalped these courses in a systematic fashion, which include the easier General Education Courses that fill up much more quickly than the difficult ones. By collaborating, the ring’s associates take advantage of their priority enrollment date to enroll in these courses. They then publicly advertise these course seats for sale through messenger apps and websites. Using social media to connect to buyers, these sellers finally scalp the courses for a handsome profit. One seller has even advertised to sell up to 71 courses for the upcoming 2017 Fall Semester.

“They hold classes for each other. Sometimes, they sell it. Some classes cost even $500, depending on how many units and the easiness of the class,” said an anonymous source to The Corsair, who wished to remain anonymous due to fear of his safety. “Let’s say you have an easy econ class, so I just say to my friend, ‘Hey, I’m looking for a specific professor, I’m looking for it, and you want to sell it. The friend just writes it in the 500 people group, and somebody responds quickly, and boom -- you get a connection... at the point, it’s just bargaining, $300, $500, whatever... it’s like a whole industry.”

Graph by Brian Vu

Graph by Brian Vu

The demand for such classes are largely motivated by their difficulty. With student enrollment down nine percent since 2009, sellers have started to target the “easier” classes. SMC’s English Department Chair Jason Beardsley said, “I’ll single out the top ten people or seven people that give unusually high numbers of A’s. Those are always the people whose classes are full early on.” Such discrepancies between grade distributions of classes targeted by scalpers and not targeted by scalpers is shown in the infographic. These graphs show that the grade distributions for the classes up for sale are higher than the ones that are not. “It’s pretty obvious to me that students are fully aware [of the nature of those courses] and very much lining up to take those courses.” This is not the first time students have exploited this discrepancy.

Hearn spoke of a previous incident that took place at SMC two years prior. Reports of students scalping reached Hearn’s office, which prompted an investigation. They discovered that students networked using social media, by advertising the class seats they held. After their investigation, the school began using evidence on the ring of students found selling class spots and old test questions.

When Hearn summoned the accused students to her office, they named others also involved. While some students under investigation were current SMC students, many have already transferred. “Some of these students who had transferred on were holding onto their enrollment dates, holding onto classes, and publishing it on social media,” said Hearn. “There was one particular person who had transferred. We found out who that person was, and made the judicial decisions that we had to make with that person.” This particular person, according to Hearn, was the ringleader. A meeting, which involved the college’s attorney, put a stop to the ringleader and his circle. Specifically in response to this incident, Hearn took these reports to the Academic Student Affair Committee during the 2015-2016 school year. Consequently, the committee added a new rule to the Code of Academic Conduct, rules that specifically establish what is considered academic misconduct. This rule, titled section V, prohibits “the sale, purchase, exchange, distribution or receipt of add codes, class seats, and academic work (Article 4410, V).” The new language and the ensuing investigations, resulted in the number of reports to decrease. “But students are smart,” said Hearn. “As soon as you plug up one hole, there’s another that pops up.” Current problems prove Hearn was right -- and these have been more difficult to crack.

The seller’s usernames are displayed on WeChat, but there is little SMC can do without specific identification. “Part of the problem is that people aren’t reporting,” said Hearn. Providers operate using code names, such as ‘Big Mouthed Monkey’. Hearn shared that, from time to time, she receives emails of students trying to expose these activities without sharing actual names. To Hearn, the search then becomes “like a drop in a bucket.”

“It’s not fair to students who do it the right way,” said Hearn of the activity. “It’s not fair to students who are waiting in line to get their classes -- it’s just not right.”

Georgia Lorenz, SMC’s Vice President of Academic Affairs, said regarding these activities, “It’s really disappointing and really frustrating not only because it’s really unethical behavior but it’s negatively impacting students who are playing by the rules... if you’re a student who’s really close to transfer and you have 10 units you need in the Spring and somebody else is there selling seats and you can’t get what you need -- that’s horrible."

When asked about how he felt about these activities, Talha Adric, an international SMC student, said, “I think this whole thing is unfair because when other people are enrolling in these classes and holding it for a third person they’re holding my right perhaps. Maybe I had the second enrollment date and I was aiming to hold that class... I think it’s really unfair for people who have no idea what’s going on.”

Hearn explained that her role is not to punish, but to educate. Referencing SMC’s Code of Academic Conduct, she lays out four possible levels of punishment for students engaged in these activities: a written reprimand, which warns the student not to continue these activities, disciplinary probation, which puts the student on notice that continuing their type of conduct will bring a harsher punishment, suspension and expulsion, both of which are able to be appealed. However, Hearn stressed that she takes a case-by-case approach when dealing out disciplinary action. Hearn explained, “Every case is very different. You may do the same thing this student does, but your cases are very different. So the consequences could either be the same, or they could be very different.”

One of her office’s biggest challenges is informing these transgressing students what they are doing is wrong. Hearn said, “I think one of the biggest problems is that people who participate in this [activity] don’t really know the consequences. They don’t know until they get in here.”

With 30 years of experience at SMC, Hearn believes these issues can best be solved through fellow students, saying that “when the students reprimand each other, the impact of it is so much greater.” But because community colleges only have students stay for two years, student initiatives fail to make lasting progress. “They try to get some ideas, they try to play out these ideas, and boom, they’re gone. You guys are here for a season, then you’re gone,” said Hearn. Yet this problem goes beyond her office, it affects the professors and student body as well.

Many are perplexed on how these activities can be properly dealt with. Dr. Beardsley says, “where do we stand? Where is the criminality in stake in this impersonation? Because frankly I don’t understand how they [impersonation services] exist. How a service that says, ‘Yes, we will take a class on your behalf and get your grade.’”

Yet criminal prosecution appears to remain unlikely. SMC Police Chief Johnnie Adams explains that if these activities break the school’s rules, they only require enough evidence to have more than 50% chance of being true. But when it comes to legal action, the case would have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that these students broke the law, which is a much more difficult burden to prove. “These kinds of cases are very complicated... that the school has to go through multiple processes to prove [legally],” Adams says. “Because [for] criminal cases, remember, you’re going to take away somebody’s personal freedoms and then pull them into custody and take away their livelihood.”