The Magic of the Zapotec

Conor Heeley | Managing Editor

Porfirio Gutierrez is on a mission to keep Oaxacan traditions alive.

Holding up a hand smeared blood red, Porfirio Gutierrez shared the ancient, often painful history behind the dye that has meant so much to the Zapotec people, that of the cochineal insect. The Oaxacan-Californian textile artist was at the Main Campus on Thursday, where he gave a compelling presentation about his art and his culture, followed by an intimate workshop on weaving with students and community members.

At the invitation of SMC Spanish professor Dr. Alejandro Lee, Gutierrez gave an hour long presentation on the history and practice of Zapotec dying and weaving, and how this traditional, indigenous art form is built on a synchronous relationship with the natural world in which it evolved.

Officially billed as a talk on “The Relationship to Climate and Artist Material,” the Zapotec weaver spoke at length about his journey from construction worker to world renowned artist, the painstaking research and experimentation in rediscovering indigenous practices, and the history and cultural significance of his art and his dye-making.

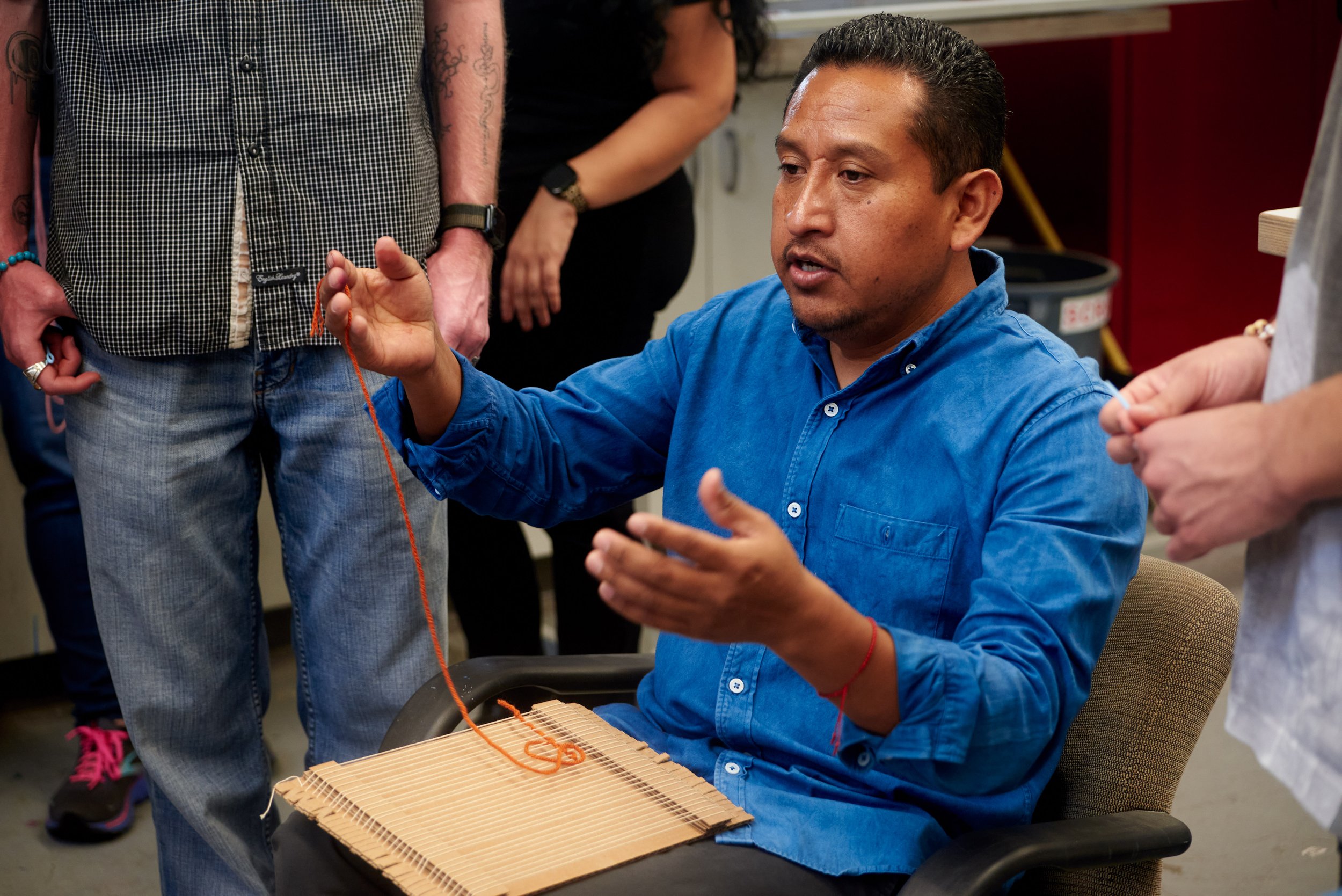

What followed this talk was an hour and a half long workshop in the Art Building, where students from the art and Spanish programs learned the basics of weaving on cardboard looms, with personal instruction and guidance from Maestro Porfirio. One of those students was Esmeralda Hernandez, an organizer of the nascent Oaxacan Students Club.

“It’s so amazing to have an Oaxacan artist on campus,” she said, noting that having him come just weeks after the college’s inaugural Guelaguetza celebration was doubly inspiring.

Sculpture professor Emily Silver worked with Dr. Lee to make the workshop a reality. “I heard that he [Gutierrez] was coming to campus, and I knew we couldn’t miss this opportunity,” said Silver, as she finished stringing the last of the cardboard looms she had constructed.

After getting everyone started with weaving, Gutierrez took a moment to rest and eat some of the Oaxacan food that had been arranged for by Dr. Lee. Reflecting on the path he’d chosen, he noted that he didn’t always consider himself an artist.

Born to a family of subsistence farmers in Teotitlán del Valle, in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, Porfirio admitted that he took his family's unique lifestyle and traditions for granted. When they weren’t working to put food on the table, his mother, a Zapotec healer was out gathering medicinal plants and dyestuffs for their weaving.

Of these dyestuffs, the most historically important, according to Gutierrez, is the cochineal. About 5 millimeters long, these insects are parasites of cacti found throughout Mexico and the southwestern United States. After the colonization of Mexico, the industrialization and farming of cochineals was the most visible success of that conquest, responsible for the deep red that has been emblematic of Spain and Spanish aristocracy for centuries.

It was through this lens that he spoke about the relationship between art and climate in his presentation in Stromberg Hall. Because much of his materials are gathered by hand in Oaxaca, like the wool for his yarn and the plants for his dyes, he is wholly at the mercy of the natural, seasonal cycles. This is why many of his rugs take seven months or more to complete, from conception to finished piece.

After leaving his village at 18, Gutierrez worked on construction sites around Los Angeles, eventually becoming a cement truck driver and then a supervisor of a cement plant. It wasn’t until he made his first visit back home that he realized what he had given up in exchange for the economic opportunity of immigrating to America.

From that point on, he dedicated his life to preserving and revitalizing the near extinct practice of weaving Zapotec textiles with hand-gathered dye stuff, a cultural tradition that stretches back before the recorded history of the Zapotec began.

Gutierrez leveraged his English and his knowledge of American institutions to view the textile archives at some of the most prominent American cultural Institutions. “The collection at the National Museum of the American Indian was really helpful in researching design and techniques,” said Gutierrez.

Gutierrez splits his time between his studios in Ventura and Oaxaca, along with a steady stream of workshops and speaking engagements at universities, institutes, and museums.

There are no other Zapotec weavers with as high a profile as Gutierrez, and for good reason, according to him.

“There are others doing this work, but in every art, there is a generational talent that comes along and defines the form,” said Gutierrez. When asked if that was him, he nodded.

Students flocked to the main campus quad for a pre-finals bunny break, complete with music, snacks and stress-relief.