From Silence to Strength

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, or Orange Shirt Day, is this upcoming Monday, September 30th. According to Sequoyah Thiessen, a Santa Monica College (SMC) student and the President of the Indigenous Scholars Club at SMC, it is a day about commemorating Indigenous ancestors who suffered through the Residential Boarding Schools: the survivors, their families, and the ones who didn’t make it out.

Thiessen, who is Ojibwe, is working with the club to spread awareness about the day, as well as taking time to remember their Native ancestors who attended these schools.

Residential Boarding Schools were government funded schools throughout Canada and the United States and run by various Christian denominations. They started in the 1800s and existed for over 150 years, the last school closing in 1996. More than 150,000 Indigenous children attended them in the United States and Canada during that time.

These schools were created as a way to take away Native culture. In a speech from 1892 Captain Richard Henry Pratt, who founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School which was one of the most prominent residential schools in the United States, said “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” when speaking about the purpose behind these programs.

“You would have your hair cut. You would not be allowed to speak your language” Seqouyah Thieesan said. They would also change the names of the kids to further separate them from their heritage. “That's actually how my grandma, who helped raise me, got her name, Angie. Angeline.” Thiessen said, “She doesn't even remember the name that she was given before that.”

The Indian Act, amended in 1920, made attendance mandatory, and “parents could be jailed if they refused to hand their children,” according to CBS News.

Daniele Bolelli is a professor of Native American History at SMC and has a master's in American Indian Studies from UCLA. When talking about the program, Bolelli said, “It’s a program of complete cultural wipeout in which you as the parent, or you as the kid, have absolutely no choice in this process.”

Tuberculosis ran rampant due to poor conditions at these schools and abuse was a common practice. The curriculum taught the kids to become workers of a lower class, such as farmers or homemakers, hindering their education further. Many Indigenous children died in these schools due to the terrible conditions, and researchers are investigating potential unmarked gravesites at boarding schools across the nation.

“Orange Shirt Day” stems from Phyllis Webstad, who recounted her story of attending one of the schools when she was 6 years old, where they took her clothes when she arrived, including her orange shirt. She said, “The color orange has always reminded me of that and how my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared, and how I felt like I was worth nothing,” according to the Orange Shirt Society.

Today, the day is now a national holiday in Canada but Indigenous people throughout the United States also observe the day. More than 523 residential boarding schools existed across the United States before 1969.

Thiessen said how important it is to have clubs like the Indigenous Scholars to connect with the culture the schools tried to destroy. “A lot of people don't realize the severity or even just the generational trauma,” She said, “Like the loss of language part. That's the reason why I started this club. When you walk around campus and you see all these other students connecting with each other in their language, it's actually kind of painful when you realize that even if you did know your language fully, the chances that you could speak it with somebody else in your community are really low.”

According to the Indigenous Language Institute, only about 150 Indigenous languages are still spoken today compared to more than 300 pre-colonization.

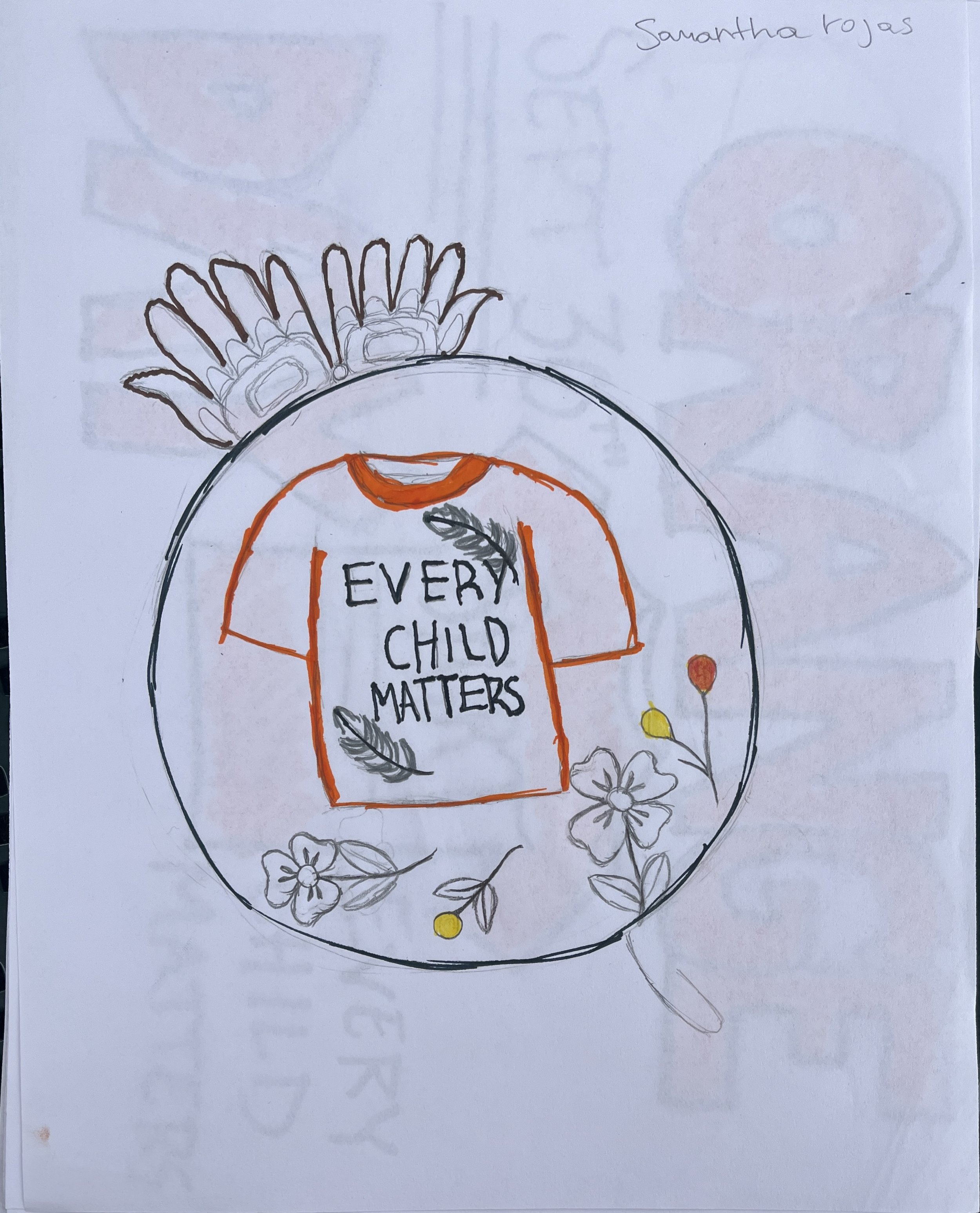

Thiessen led the Indigenous Scholars Club in creating posters to spread awareness of the day. “What it's about for me is just having awareness because a lot of people aren't... I don't think that they understand the severity of the boarding schools,” She said. She wants everyone to remember that this is not that far in our past, there are still many Indigenous people alive today that went through the boarding school system.

The club's Vice President, Aisa Ortiz, is also fighting for their history to be told. Ortiz is K’iché from the Mayan people on her dad’s side and Apache and Tepejuan on her mom's. She said she realized how much she missed her culture when she saw pictures of people from her tribe for the first time. “There were specific features that I was like, oh, my God, that looks like me,” she said.

Since the club was founded last spring, more than 70 people have shown interest, and they have made a point to welcome all Indigenous communities. “It really warmed my heart that a bunch of different girls saw representation,” said Ortiz, “they saw they're not the only ones here from another foreign place.”

Though both the Canadian and United States governments have taken some steps to account for the trauma endured in these schools, Bolellie notes the real impact is not with something symbolic, but with action. He said, “I think on a practical level there are obviously real issues that Indigenous communities want to address, like the whole theme of Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women. Put the gigantic effort into further investigation into cracking down on some of that.” This refers to the movement that brings awareness and calls for action to the large number of murdered and missing Indigenous women in recent years.

These schools have also had a lasting impact on indigenous cultures. “A lot of times to get through something, you kinda just had to swallow it,” said Thiessen. She said her Grandma rarely spoke about her time at the school, and Ortiz noticed the same behavior with her Mom. It was how their ancestors coped, but the impact did not disappear.

Ortiz said, “Alcoholism and substance abuse are really prevalent on the reservations and in Indian communities. But that's because we forget to realize that these are generations and generations of mourning.”

According to the American Addiction Center Native people, “experience much higher rates of substance abuse compared to other racial and ethnic groups,” The 2014 White House Report on Native Youth also showed suicide and PTSD rates as three times that of the general public.

Thiessen and Ortiz are working with the members of their club to heal as a community and continue spreading all the wonderful parts of Indigenous communities that persist. On the day, they plan to wear orange to show their support and lead an ancestral prayer with the group. “It's almost like a moment of silence, but in a day. I'm gonna take it easy that day. I'm gonna really be kind to myself that day. And, I think just the ancestral prayer is really important just to acknowledge the ancestors and tell them that we understand them and we see their pain,” Thiessen said.

They encourage anyone who wants to wear orange on Monday, Sept. 30, to show their support and awareness of what went on in the residential schools, as well as everything that still needs to be done.

“I'm here.” Ortiz said, “I'm not forgotten, and my people don't have to live in the shadows. And it's possible for them just as much as it is possible for me. Because that opportunity and dream are constantly stolen.”

For more information and resources on further events the club is hosting, check out their Instagram at: @indigenous.scholars