Blind Eyes and Genocide

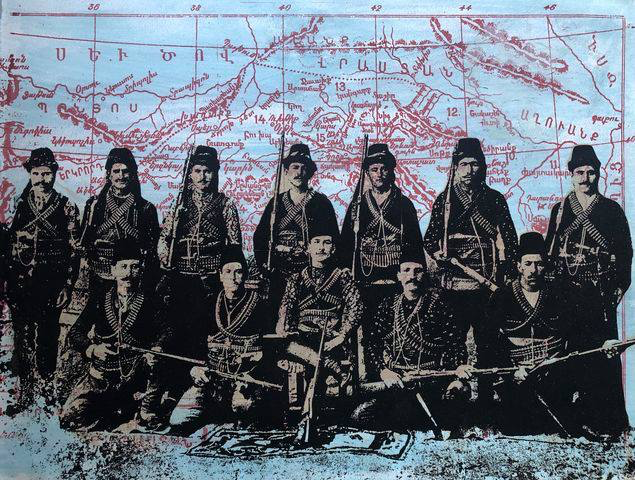

Print by Roxanne Alexanian, using a photo of members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (also known as Dashnaks) from a book published by the Ottoman government in the 1920s. According to the artist, "There are a bunch of these photos in the book. But I looked at them as heroes defending their families and their country rather than terrorists. This was one of the images from the book so I layered the screenprint of them over a map of old Armenia (that is now Turkey). I printed the dashnaks in transparent ink so that you can see the map through their skin. The map lines mimic veins- the country is in their blood- and their life."

The first time I remember having the atrocities my relatives survived explained to me was through a reprimand. My dad reworked the “Eat your food, there’s starving children” line into “Eat your food, Meds Babi (Great Grandpa) had to boil horse s---during the genocide so he could eat the undigested oats.”

Another story I heard was about the sparrows; how my great grandpa used his slingshot to kill and eat them whole when he was trying to survive an unforgiving desert (later in his life, he would rescue sparrows from cats and punish my dad and uncles for shooting them down for fun). I learned about the genocide, also known as the Meds Yeghern (Great Catastrophe), through family. My formal education taught me nothing about the genocide until the 11th grade: an aside mentioned in two dry paragraphs.

It’s not my intention to rehash what’s been proven more eloquently and thoroughly; historians from around the world, Turkey included, have published acknowledgements of the Meds Yeghern and details outlining its categorization as a definitive case of genocide. Recommended reading includes "A Shameful Act" by Taner Akçam, "Ambassador Morgenthau's Story" by Henry Morgenthau Sr., and the debates of House Resolution 398 from Sept. 14, 2000.

The Turkish government, however, refuses to acknowledge the Meds Yeghern as a genocide. Their education system paints Armenians as traitorous defectors who were a threat to the Ottoman Empire, and they continuously lobby foreign governments to prevent the spread of public knowledge about the genocide.

Recently, Turkey’s Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has sought to minimize the experiences of Armenians during WWI, while severely punishing those who speak out against their narrative. Armenians around the world look to the issue of genocide acknowledgement as a unifying cause, and many still harbor the same biases against Turkish people as their great grandparents.

Attempts at Turkish-Armenian diplomacy have been largely ineffectual since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and Armenia’s subsequent independence. Armenian history during the time of the USSR isn’t rosy either. While the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic was neutral with Turkey, decades of second-class citizenry for Armenians and other ethnic minorities living in Turkey during the time helped paint the backdrop for a string of anti-Turkish terrorist attacks in the early 1980s by Armenian liberation groups. Since 1991, conflict over territory, the lack of sustainable energy in Armenia, and a permanently closed border have led to little diplomatic progress between the two countries.

When Turkey attempted to join the European Union, a requirement for their acceptance was acknowledgement of the Armenian Genocide. In 1991, Turkey refused to open their border gates until Armenians waived their attempts at international genocide recognition. Neither of these policies resulted in an agreement.

The term “collective trauma” defines the psychological effects on a large group or society common after a traumatic event. It’s often intergenerational, and continuously influences how a group of people responds to threats, relates to out-groups, and forms identity. Perpetrators of collective trauma respond in a myriad of ways: denial, reconstruction, erasure, or acceptance of responsibility. Most commonly, victim groups grasp onto trauma as part of an ethnic identity that spans over a diaspora.

According to a study titled “Collective Trauma and the Social Construction of Meaning” by Gilad Hirschberger, “Historical closure may convey benefits for both victims and perpetrators when closure is part of a reconciliation process. In this case, closure may indicate a symbolic departure from the past that entails the construction of consensual memory about the conflict.”

Armenian and Turkish officials alike have stated that the discussion of the genocide (or lack thereof) shouldn’t be an issue when it comes to establishing basic normalization policies between the two countries. However, the events of the early 20th century are still fresh in the minds of Armenian and Turkish citizens alike, as well as descendants of the Armenian diaspora who have kept the history alive. The understanding of the genocide is fundamental to the relationship between Armenia and Turkey on both a country-wide and individual level; without the recognition of mistakes, there will not be trust between the two countries or their people. Without a “construction of consensual memory,” misinformation will continue, prejudice between the two groups will continue, and the patterns that lead to large-scale violence will not be taken seriously before it’s too late.

While many states, cities, and organizations in the United States have publicly stated that the Meds Yeghern fits the definition of genocide and should be historically recognized as such, the federal government has not. And while information about genocide is part of required U.S. curriculum, only 15 states’ education systems actually mention the Armenian Genocide at all.

An argument often made against the American governments’ acknowledgement of the Armenian Genocide is that the relationship between Turkey and America is too essential to our operations in the Middle East, and bringing up the genocide would only serve to antagonize our ally. However, due to Ankara's repeated nonobservance of U.S. policy, there's no longer a strategic relationship between Turkey and the U.S. outside of NATO agreements. Relations between Turkey and America are already deteriorating, and so are the Realpolitik arguments of strategic genocide denial. And even if things were great between us, in the words of New Jersey Representative Christopher Smith during the proceedings of H.R. 398, “Friends do not let friends commit crimes against humanity or refuse to come to terms with them once they have happened.” The result of perpetuated ignorance is repetition, and today, genocide continues in the policies of Prime Minister Erdoğan.

As of Oct. 9, the Turkish army is invading the disputed “safe zone” near the autonomous region of Rojava on the Syrian-Turkish border, currently occupied by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and thousands of civilians. The SDF, who have previously assisted the U.S. in anti-ISIS campaigns, are a coalition of predominantly Kurdish militias native to the area. The Turkish government has a history of discrimination and violence against the Kurdish people, which they justify today by conflating the entire ethnic group with terrorists. Turkey claims that their plans to clear the area of its current inhabitants is to make room for the relocation of three-million Syrian refugees currently living in the country, raising alarms about possible human rights violations and the past pitfalls of declared “safe zones.” The SDF has criticized the idea as a form of demographic war. President Trump pulled U.S. support from the area, and has so far refrained from assisting either side of the conflict that’s ensued.

Representatives and pundits across the political spectrum quickly condemned Trump’s decision as a betrayal to a source of loyal support against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (and a wrench thrown into U.S. efforts to continue suppression of ISIS). However, it also fits into a pattern of America’s indifference towards the contingency of ethnic cleansing and war crimes committed by our global allies.

Another hesitation comes from the idea of America opening a proverbial can of worms with genocide recognition; if our government were to censure the actions taken by the Ottoman Empire in 1915, they’d set a precedent and would have to reflect on America's extensive history of similar crimes against indigenous people or the long history of chattel slavery. Or maybe even reflect on some acts today that are cut from a similar cloth – the kind a hairsplitter wouldn’t define as actually ‘genocidal,’ like mass incarceration, internment camps, or the separation of families at border facilities.

Maybe some reflection is a good thing.

Turkish lobbyists frequently plead with the American government not to "throw stones in glass houses." However, if hidden within those fragile aphorisms are centuries of prolific massacre, I’d argue it’s time some glass was shattered. Genocide isn’t necessarily the result of decades of conspiracy; sometimes it's just the right combination of greed, paranoia, apathy, and a lack of oversight. Official Turkish record still maintains that the strategic killing of civilian Armenians was entirely geopolitical. Unless we retrace the steps that pushed "national security concerns" over the edge into wholesale slaughter, it's going to happen again. It already is in Rojava.

American acknowledgment of the genocide -- one that comes from the federal government -- would bolster a globally-recognized historical record of the event. It would help improve preventative education about genocide in America, and it would further the discussion for a mutually agreed upon history between the perpetrators and victims of collective trauma. The Armenian Genocide has been studied as a defining event in the history of human rights violations, and needs to be recognized at such. Establishing accountability for the past is essential to preventing a continued cycle of genocidal acts from being swept under the rug. No more band-aids on bullet wounds.