Prison Architect: Have your guilt-cake and enjoy it too!

Looking at the 2014 Annual Letter to Shareholders for the Corrections Corporation of America – the largest player in the privatized prison industry – shows that business is booming. Profits, demand, and stock dividends are all up over 2013 and only expected to rise higher as new contracts to build more facilities come in. Life is good if you’re a part of this growing industry that houses around 8% of the US prison population (currently at about 1.5 million prisoners, according to Bureau of Justice statistics), and it’s only going to get better as the industry gets an even larger percentage.

Among the many groups that hope that outcome doesn’t come to pass is the ACLU. They claim that the industry serves little in the way of the public interest and only hurts those who are incarcerated. It's an idea that a recently published study from the University of Wisconsin agrees with. A review of 8 years of data showed that, on average, inmates held in private prisons were jailed longer and more prone to recidivism, negating much of the potential savings to the public for using them, since it is in fact the tax payer who pays these corporations to house our nation’s inmates.

Needless to say, the mere concept of the privatized prison industry presents a thorny issue prone to spark acrimonious debate wherever it shows up. It's fertile ground for any kind of art to thrive, but to date very little actual media other than documentaries have been produced around the topic. A fact that changed last week when "Prison Architect" hit version 1.0 and was finally released officially for PC.

That such heady subject matter is embraced as a videogame might be surprising to people. After all, few games attempt to tackle real-world issues, and more importantly, if there is fun to be mined from such heady subject matter, should it be?

Developed by humble UK studio Introversion Software, "Prison Architect" casts players into the role of CEO for an incarceration corporation that designs, constructs, and manages prisons. You have complete control and freedom to do what you please with a parcel of land; whether you build a jailhouse that strives for strict principles of punishment and discipline or a big house of healing and reform is up to you.

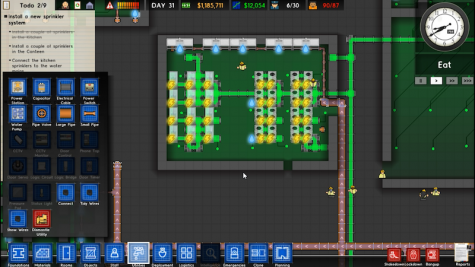

As the “architect” implies, the heart of the game lies in construction. The easy to use point and click interface allows for quickly drawn lines of walls, fences, and roads as you construct complexes as practical or fanciful as you’d like. But there’s quite a lot of bureaucratic management as well – arrays of menus let you fiddle with every aspect of your joint, from the daily schedules of your captive population to the patrol routes of your guards – all while you try to stay out of the red, since most every action you take deducts from your bank balance.

The graphics are colorful, flat 2D ideograms of people and objects, a simple style critical to keeping the framerate smooth as intricate webs of systems have potentially thousands of AIs running during the game. The primary way you engage these systems is in the core Sandbox mode, where you build prisons, sell them off for funds to build more, then upload them so others can get a glimpse of your convict cage craftsmanship. But it’s the other two main features that are potentially more interesting: a multi-chapter Campaign mode and the script-flipping Escape mode.

Escape mode puts you into the shoes of a prisoner sent to your jail (or one you’ve downloaded) and tasks you with figuring out how to tunnel your way to freedom like Andy Dufresne in "The Shawshank Redemption." This grants a new perspective on the game’s systems and your own handiwork along with more direct involvement, but the unique mechanics are too simple for it to be much more than a diversion.

It’s in the Campaign mode where this otherwise superficially colorful game generates more somber themes. Primarily acting as a series of tutorials on all of the game’s features, each chapter is framed around unique characters and tells a complete story about them. While they draw heavily from prison film tropes, these vignettes still consistently manage to generate pathos and a sense of depth to the otherwise flat cartoon people that inhabit this game, as well as subtly reinforcing a wry tone of suspicion about the morality of the fundamental practice that is private prison management.

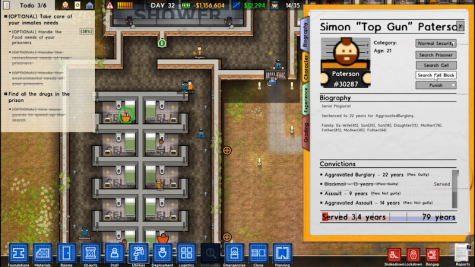

Other games with messages tend to hit you over the head with them, but such bluntness is unnecessary here – any commentary the developers want to make is imbedded in the most intelligent way: through game mechanics. It’s in the little things where this becomes apparent, like the fact that your primary way to survive early on is in exploiting extensive government grants, forcing the player to realize that the vast majority of not just the care, but also the building of private prisons is subsidized by the taxpayer. Or there's the sobering fact that only the prisoners get names, personal details, and families – they’re the real characters, and your staff members are endlessly replaceable drones that are extensions of your (corporate) power.

Such subtly inserted commentary is critical here, because on the surface of it, "Prison Architect" is no different than its subject matter – a cash-in on the back of a system that’s morally ambiguous at best, just in the form of a fun videogame. And it is fun. Well-honed building and management mechanics balanced over years of development ensure that this is testament to the builder genre.

Having fun over such a potentially morbid issue could easily leave players with a sense of immense guilt, but the trick the developer is pulling off here is that by playing both sides, you end up learning just how potentially dangerous the private prison system can be while you enjoy simulating it.

Ultimately "Prison Architect" isn’t going to shake the foundations of the Prison-Industrial Complex down or change the world, but the people who play the game and end up learning about the topic might just be able to down the road.