Abbot Kinney: The Ugly Face of Gentrification

If there’s one street that embodies the gentrification of Los Angeles neighborhoods, it’s Abbot Kinney Boulevard in Venice.

For years, Venice, Calif. was synonymous with laid-back surfers, a lively arts community, and gritty streets that many diverse people called home. It was not a polished, high-end part of town, but it was, perhaps, the most fun and interesting. Venice was a place where people could let loose, fly their freak flags, and break the rules.

In the late 80’s, when builder, developer, activist and artist J. Kevin Brunk became the “unofficial beautifier” of Venice, he planted the palm trees, revived the Abbot Kinney Festival and spearheaded the renaming of West Washington Blvd as Abbot Kinney Blvd, in honor of the late Abbot Kinney who had also seen the beauty in this seaside spot almost a century ago. Since then, Abbot Kinney Blvd has been on a rampant path to gentrification and subsequent widespread popularity. Over the past 5 years, it has become one of the hottest spots in the country and in 2013 GQ Magazine named Abbot Kinney as the “Coolest Block in America.”

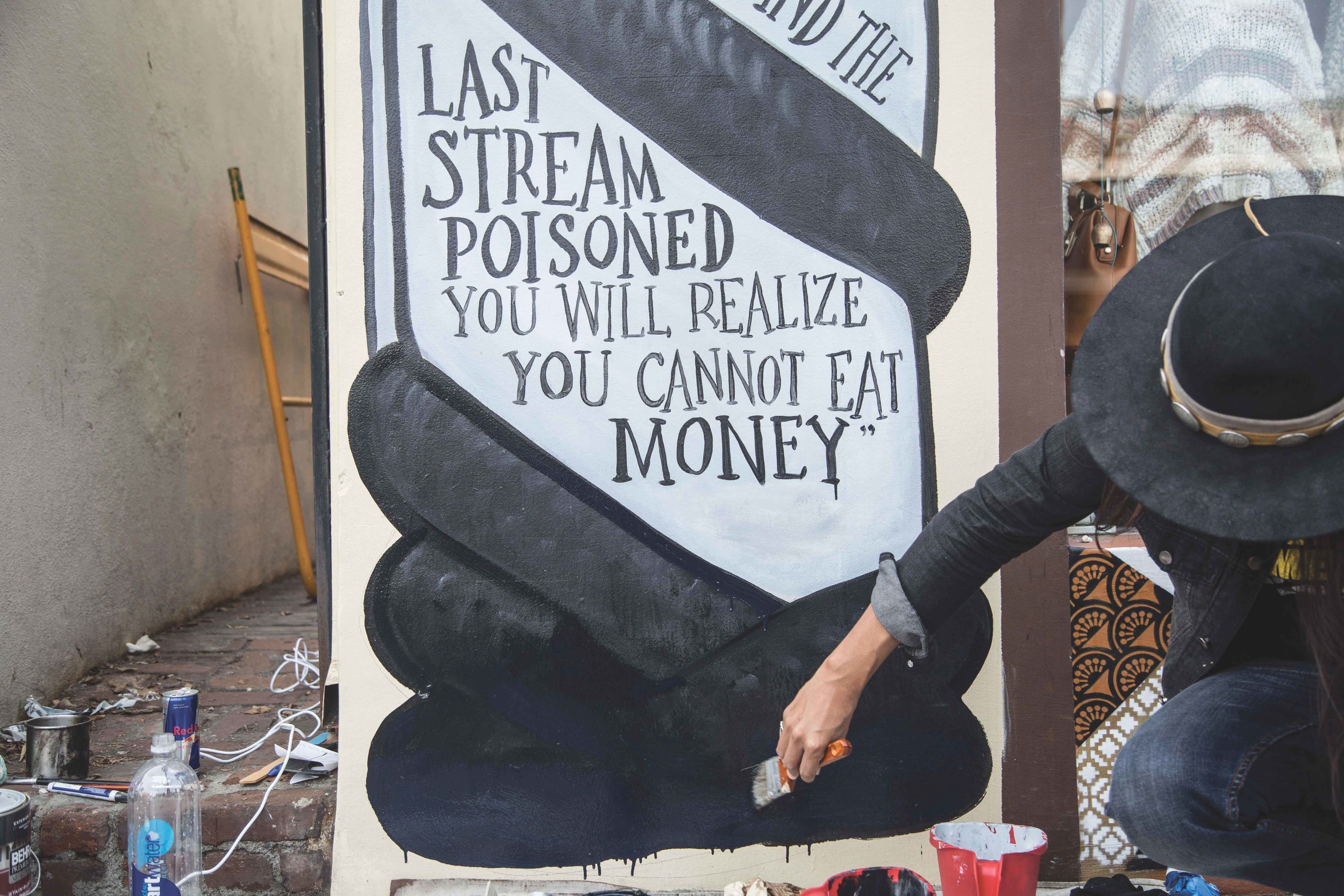

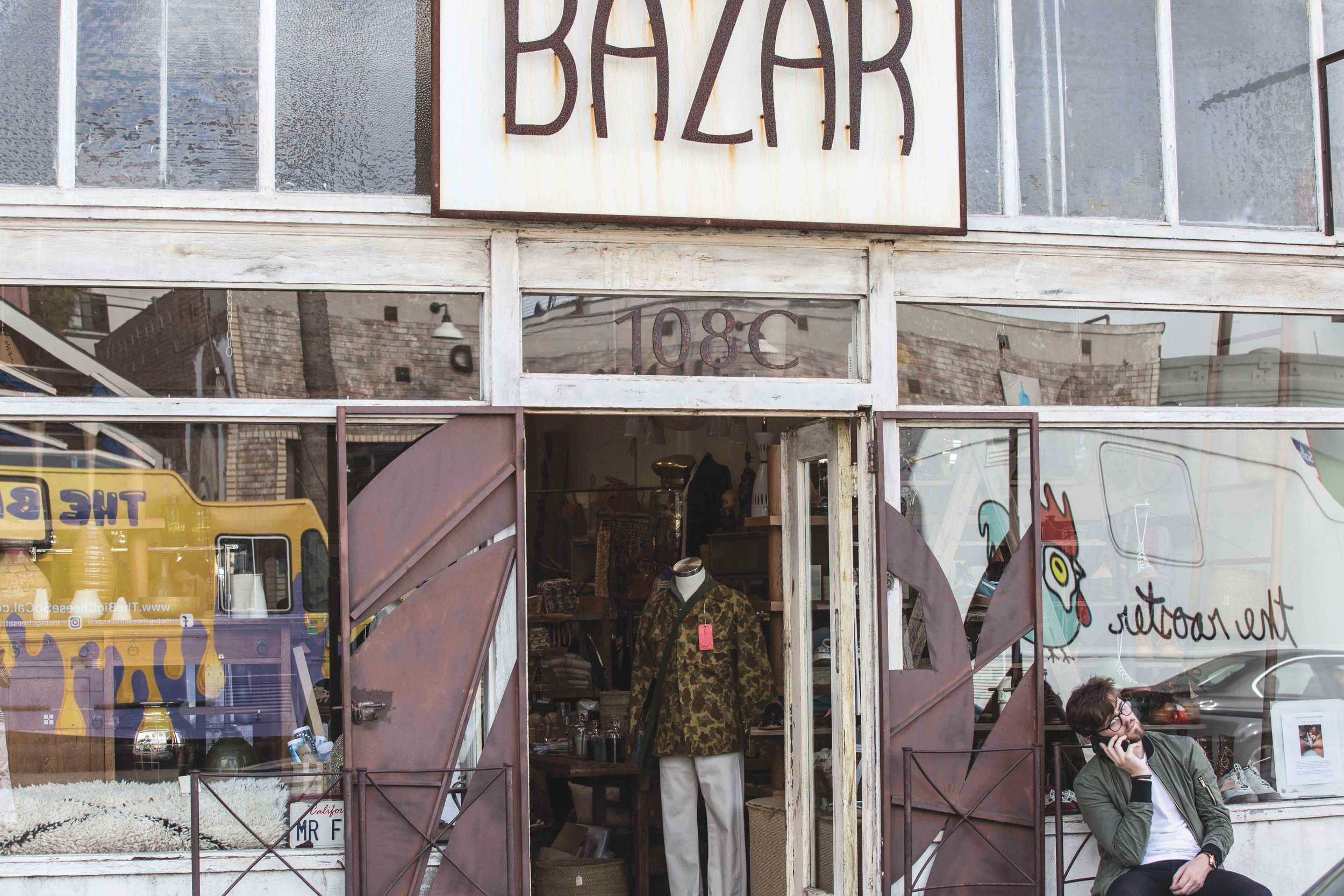

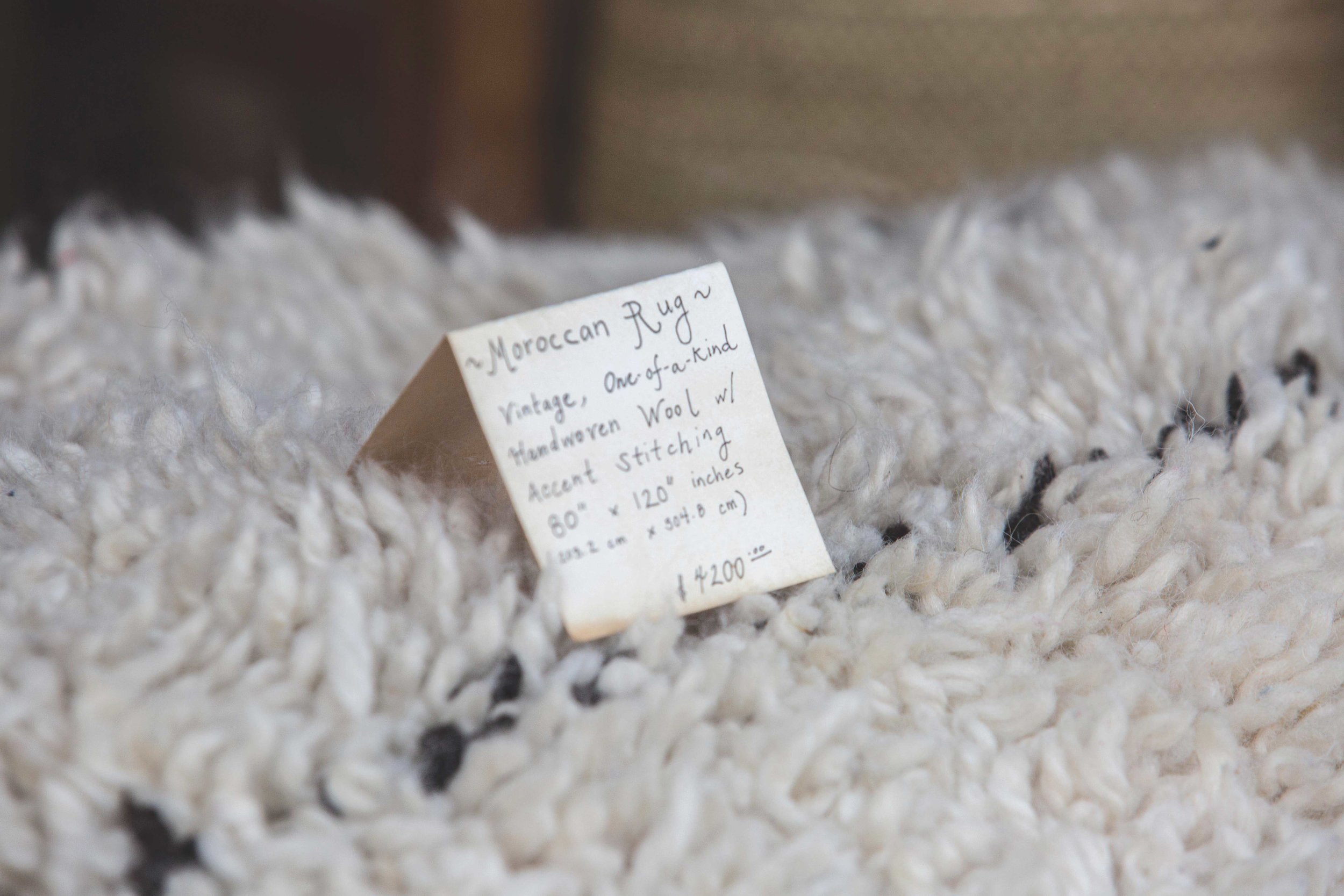

But, as with all areas that experience change, what some saw as improvements, others saw as destructive steps towards the breakdown of what made Venice special in the first place. The funky, iconic institutions like Surfing Cowboys, purveyors of surfing iconography, and The Roosterfish, West LA's only gay bar, are gone now, as are the homeless people and the bohemians. With an increasing number of chain stores and skyrocketing rents, Abbot Kinney is ‘brand new.’ No longer a haven for the eclectic mix of art studios, funky boutiques, junky antique stores and cheap restaurants, it is instead a commercial real estate boom for a new demographic of wealthy locals. Google and Snapchat now rule this turf, and have brought with them new inhabitants with deep pockets stuffed with money. Locals like Brunk and older residents who have resisted the commercialization of Abbot Kinney haven’t hoisted a white flag in defeat, but it is clear that they have lost the war against big business in Venice.

It’s a little heartbreaking. When people like Brunk came to Venice they experienced a burgeoning scene of art, music and culture and he was inspired to preserve the beauty in what he found. Today, Brunk somehow feels responsible for igniting the flame of change because he planted that first palm. He had no idea that his idea of beautification would morph into “the ugly face of gentrification.” Today, Abbot Kinney’s shiny signs, polished restaurants and utterly unaffordable shops are not what he imagined would ‘live’ there. And the people are shiny and new too, and, according to Brunk, “don’t appreciate or understand the history and culture that they are trampling.”

Locals like Brunk who feel like interlopers now avoid Abbot Kinney, for its former uniqueness has been replaced by overpriced commercialism. And Brunk finds it hard to visit without pondering what once was. He prefers to stroll the back alleys off the strip rather than the shiny new boulevard. In a ironic twist, as an original beautifier of Venice and in particular of Abbot Kinney, Brunk can no longer afford the land he once owned and has become economically and culturally displaced.