The Electoral College

Infographic by Johnny Neville & Carolyn Burt | The Corsair

While puzzling to those unfamiliar with it, the Electoral College is more American than apple pie.

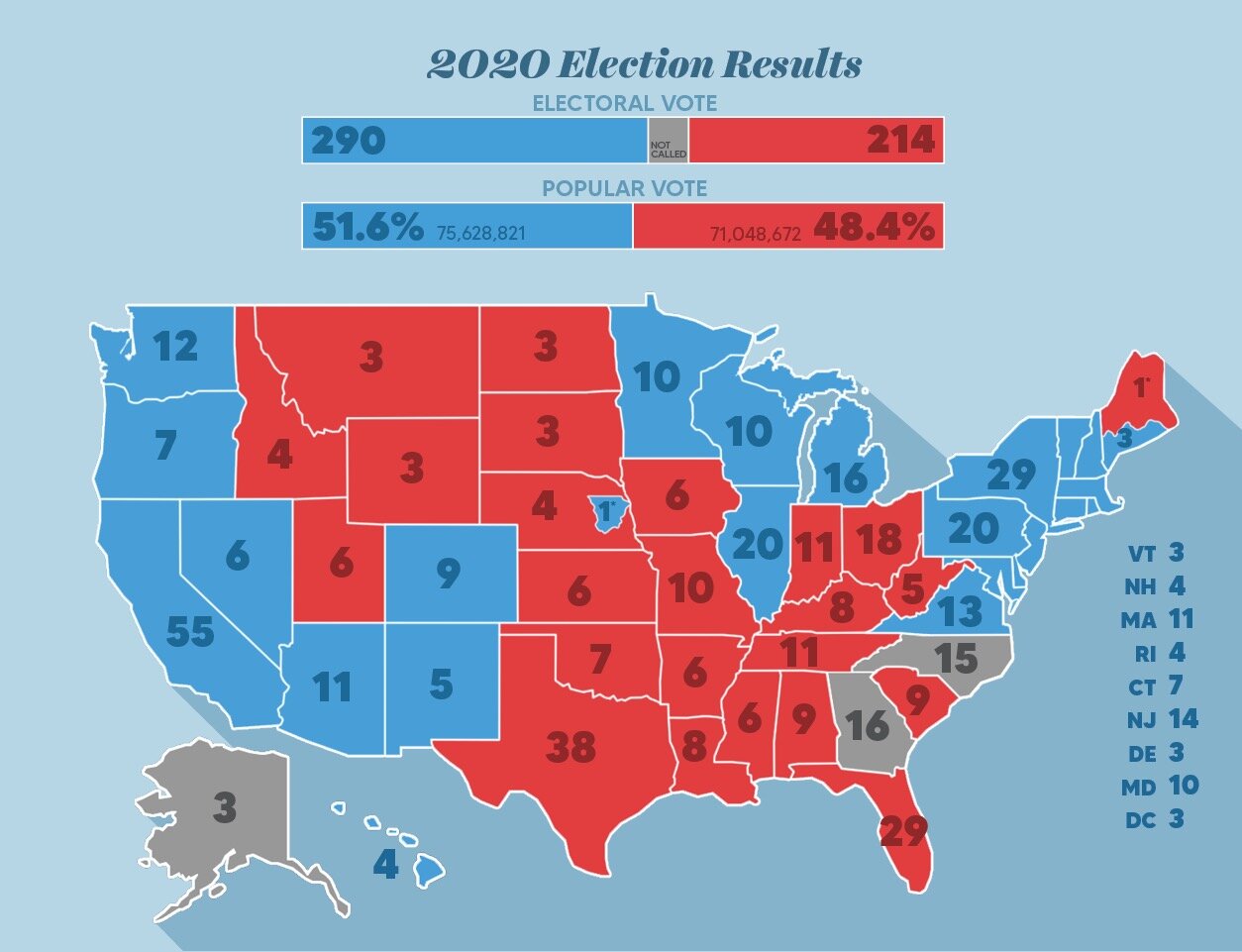

As the 2020 election votes continue to be counted in many areas of the country, Democratic presidential candidate Joseph R. Biden has been deemed by credible journalistic sources to have reached 270 electoral votes, thereby becoming President-elect. He will be sworn in as the 46th president of the United States at noon on Jan. 20, 2021. Critical to Biden’s victory was his performance in the key Upper Midwest “Blue Wall” states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. President Donald Trump owed his 2016 Electoral College victory over Hillary Clinton to those same three states, winning them by a combined margin of less than 80,000 votes.

Unlike elections for governors, senators, and other federal political offices, Americans have never directly voted for their president. The Electoral College is the official name of those individuals who cast each state’s official votes for president — 538 people in total. Each individual state has a certain number of electors, based on the state’s population and corresponding members of Congress. For example, California leads the nation with 55 electors, due to its having the largest population in America. Wyoming, the state with the smallest population, has a correspondingly-low three electors.

The specific electors are chosen by political parties in each state, with the states empowering those individuals to cast their electoral votes for the candidate who has won that state’s popular vote. The two exceptions are Maine and Nebraska, who determine their electors based on separate votes in various districts of the state. Although electors can technically ignore their state’s popular vote and cast their votes for whomever they wish, it rarely happens, and has never affected a presidential election. Many states have passed legislation that penalizes these “faithless electors” with fines and imprisonment if they go against the voters of their state.

The presidential candidate with 270 or more electoral votes becomes the next president. In the unlikely event that neither candidate reaches the 270 threshold, the U.S. House of Representatives decides who becomes president, while the U.S. Senate votes on who becomes the next vice president.

The reason for creating such a complex system of electing a president stems from what existed before: 13 separate and independent British colonies. Although the colonies eventually came together under the banner of breaking free from their British roots, they were heavily divided on what system of government should come after. The Founders intended on not just gaining independence, but creating a sustainable government in its wake. The question remained of how to convince all 13 entities to agree upon what would come next.

With the Industrial Revolution in its infancy during this time period, the southern slave states correctly predicted what was to come. While the agricultural giants of the South had overall populations comparable or greater than those of many northern colonies at the time, much of their numbers were made up of slaves. Those states did not count slaves as people, neither socially nor legally. Colonies like the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia knew that as time went on, the jobs created by new technology in places like Massachusetts and New York would eventually give their northern counterparts greater power in a federal power-sharing government, if population was the sole decider in how much representation each state got.

The Founders eventually came to a series of compromises. Each state would be represented by two Senators at the federal level, which at the time would be chosen by state governments. U.S. Representatives would be allocated to each state based on total state population, to be chosen by direct election voting of the people. The Three-Fifths compromise was instituted to give southern slave states more representation in the House, counting three out of every five slaves as a person for federal government representation purposes only. For the presidency, a group of individuals known as the Electoral College would be tasked with the actual voting of the next president, with the number of electors once again based on that particular state’s population.

Critics of the Electoral College argue that it is fundamentally undemocratic to choose a president based not on the popular vote of the American people, but instead on an antiquated electoral system set up hundreds of years ago to appease slave states. Supporters of the Electoral College argue that if it were abolished, less populated states would become relatively inconsequential and therefore ignored by political parties and politicians.

While roughly two-thirds of Americans believe that whoever wins the popular vote should become president, based on recent Atlantic/Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) polling, the actual chances of that happening are slim-to-none in the currently polarized political landscape of the country. Replacing the Electoral College would necessitate a new Constitutional amendment, which would require supermajority votes across federal and state governments. Two-thirds of the U.S. Senate, two-thirds of the U.S. House of Representatives, and three-fourths of state governments would need to vote for a Constitutional amendment to be ratified. The last time those thresholds were reached was 1992, with the last significant amendment being adopted in 1971.